Blog Overview

I started blogging again in July 2023 after some shifting of my job responsibilities, and my children growing up which gave me a lot more discretionary time. I do this for me, but I hope some others find my posts interesting or useful in some way.What Are Stocks Really Worth - Here are Some Thoughts On Price to Earnings Expansion

12/11/2025 by Alan

Post Content, Images & Videos

P/E Ratio Expansion

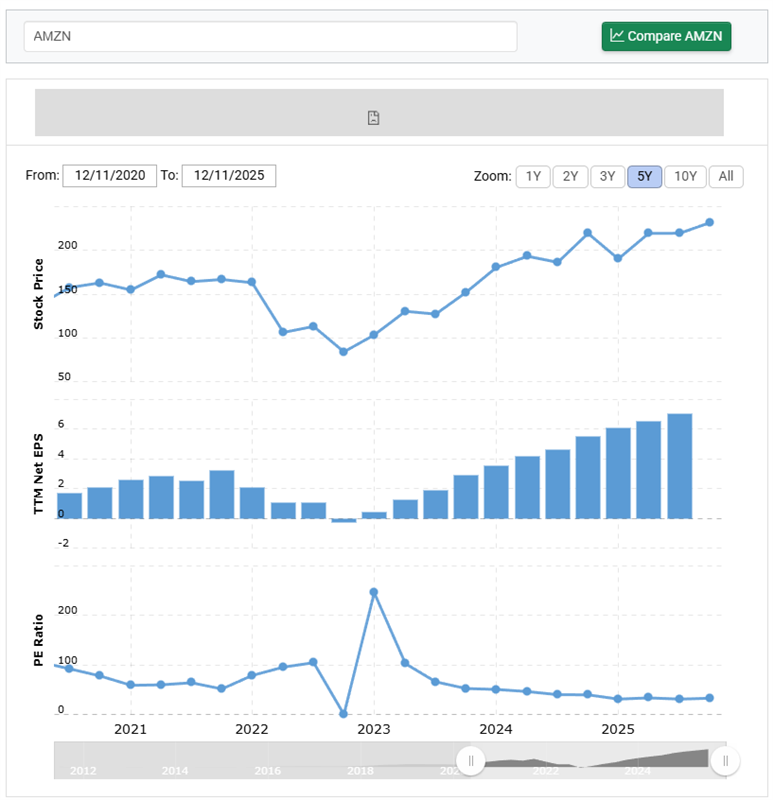

When stocks rise very quickly, their prices often run far ahead of the company’s actual earnings growth. In these situations, investors are usually reacting to momentum, hype, or optimism rather than the firm’s future earnings potential. For example, in recent years we’ve seen companies surge in value despite producing only modest profits—or even losses—creating a disconnect between price and fundamentals. As the stock climbs without corresponding earnings increases, the valuation multiple (such as the P/E ratio) expands, making the stock more fragile and increasing the likelihood of future price declines if expectations aren’t met.

High P/E ratios can and often do come crashing down. History is full of examples where lofty valuations could not be justified over time. The dot-com boom of the late 1990s featured countless companies trading at extreme multiples before collapsing. More recently, meme stocks like GameStop and AMC saw their prices disconnect from their underlying earnings, leading to sharp reversals. Even major tech companies have experienced steep drops when exuberant valuations corrected back toward reality. These examples highlight how dangerous rapid P/E expansion can be when not supported by real, sustainable earnings growth.

1. P/E Expansion (Price-to-Earnings Expansion)

This is the closest match to what you described.

- The price rises faster than earnings, causing the P/E ratio to grow.

- The stock becomes more expensive relative to its earnings.

- Future returns often decline because the company must “grow into” that high valuation.

This is why many analysts say:

“Future expected returns are lower when starting valuations are high.”

2. Multiple Expansion Risk

This refers to the risk that a stock’s valuation multiple (P/E, P/S, EV/EBITDA, etc.) is artificially high and could contract in the future.

- Stock goes up because of hype, not earnings.

- Increases future downside risk.

- Even good earnings may cause the stock to fall if the multiple compresses.

3. Valuation Bubble

Used when the expansion is extreme and not tied to fundamentals.

Examples include:

- Dot-com stocks (late 1990s).

- Meme stocks.

- Certain AI stocks during strong hype cycles.

4. Greater Fool Theory

This is a behavioral explanation, not strictly a valuation term, but it is very relevant:

A stock rises because investors believe they can sell it to a “greater fool” later — even when fundamentals don’t justify the price.

Post Metadata

- Post Number: 335

- Year: 2025

- Slug: what-are-stocks-really-worth-here-are-some-thoughts-on-price-to-earnings-expansion

- Author: Alan

- Categories: Financial

- Subcategories: Investiong

- Tags: pe-expansion

- Keywords: pe-expansion

- Language Code: en

- Status: published

- Show On Homepage:

- Date Created: 12/11/2025

- Last Edited: 12/11/2025

- Date To Show: 12/11/2025

- Last Updated: 2025-12-11 18:54:15

- Views: 0

- Likes: 0

- Dislikes: 0

- Comments: 0